Double-Entry Bookkeeping as a Directed Graph

08 Apr 2024My Journey into Accounting

In the past couple of years, I’ve been working in billing and payments at Justworks. This experience introduced me to the world of bookkeeping and accounting in ways I didn’t expect: I took a course and read a textbook in accounting, adopted plain text accounting for my personal finances, and worked in a double-entry ledger system.

Being such a fundamental part of the human experience, accounting has been around for literally millenia. It fostered mathematical and language development. In some cultures, it even predates written language. For this reason, it’s not surprising that accounting uses a very particular vocabulary and set of concepts that can be intimidating to a newcomer. Credits and debits. Assets and liabilities. Balance sheet. Ledgers and journals.

It took me a while to get used to these things. But once I did, I realized they aren’t that difficult. Maybe it is just a matter of finding the right way to explain them.

This series of articles is my attempt to capture some of my “a-ha” moments while learning accounting. Hopefully, it will help someone out there grasp these ideas in a more intuitive and modern way.

In this first article, we’ll start with the basics: bookkeeping.

Disclaimer: in this article, I’ll simplify some concepts and use slightly different terminology than traditional accounting for didactic purposes. If you’re an accountant, please bear with me.

Bookkeeping Without Ledgers

At its core, accounting is about keeping track of countable things over time. Some of the oldest documents archelogists have found register quantities in old societies: food, animals, people, money. Nowadays, accounting is usually interested in tracking money, whereas other areas (such as inventory management or the census bureau) count the rest. For the rest of this article, we’ll focus on money.

Let’s start with a very simple example. Imagine you’re in a small town with two people: Alice and Bob. Alice has $100 in her pocket and Bob has $50 as of January 1st, 2024. We’ll record this data in a table as follows:

| Person | Amount |

| ------ | ------ |

| Alice | $100 |

| Bob | $50 |

If nothing changes, our job is done. We just need to go around town and ask each person how much money they have, tabulate the data, and store it in a safe place. Badabing, badaboom!

But money is meant to be spent. Alice is studying for her finals and needs to buy a book. She notices Bob has one copy and proposes to buy it from him for $20. Bob is happy to sell her the book he hasn’t used in a while and cash in the extra $20. Great deal!

Now that money has changed hands, we need to update our records. Alice spent $20 and Bob received the same amount. Let’s update our table.

| Person | Amount |

| ------ | ------ |

| Alice | $80 |

| Bob | $70 |

Before proceeding, let’s name a few things. In our records, Alice and Bob are accounts, i.e., places where money is stored. The amount of money in each account is called a balance. Saying that Alice has $80 is the same as saying that the Alice account’s balance is $80 as of February 1st, 2024.

Definition 1: Account

A place where money is stored.

Definition 2: Balance

The amount of money in an account at a given point in time.

Every month, we can go around town, ask people how much money they have and write it down. We’re basically creating a snapshot of the town’s financial situation monthly. (Surely, most people will be annoyed by this breach of privacy and I would probably be arrested for stalking, but let’s ignore this for now.)

What kinds of questions can we answer with this data? Actually, many!

- How much money does each person have?

- How much money has each person spent or gained over time?

- Who has the most money?

- Who has the least money?

- How much money is there in total in the town?

Our records are simple but useful.

Now, consider Alice comes to us one day and asks “How come I have $80? I thought I had more!” Unfortunately, all we can answer is “That’s what I have written down” with our current data. We can’t tell, for instance, whether Alice initially had $0 and received $80 or if she had $10,000 and spent $9,920.

Why is this so?

Well, we’re only keeping track of the current balance of each account. Because we erase the old balance and replace it with a new one, we don’t know exactly what happened to that balance over time. We lose the changes that happened between snapshots.

Could we do better?

Of course! Accountants have dealt with this problem for centuries and they have a solution: ledgers.

Bookkeeping with Single-Entry Ledgers

Let’s now think how we could keep track of the historical changes in a systematic way. One way to do this is to write down each update as it happens, not only the balance in a certain date.

To do this, we’ll change the table a little bit. For example, we write down that on January 1st, 2024, Alice had $100.

| Account | Description | Date | Amount | Balance |

| ------- | --------------- | ---------- | ------ | ------- |

| Alice | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $100 | $100 |

We added some columns to the table:

- Description: A human-readable explanation of the transaction (e.g. what it is about, who got paid, a reference number, etc).

- Date: When the transaction happened. Besides ordering transactions, this field can be used to group transactions by period (e.g. monthly reports). It can be enhanced with time information (e.g. hour, minute, second) if needed.

- Balance: The balance of the account after the transaction. This field is redundant, but it’s useful when inspecting the data.

So far, so good.

Now, let’s take a look at how we can write down that Alice bought the book from Bob.

| Account | Description | Date | Amount | Balance |

| ------- | --------------- | ---------- | ------ | ------- |

| Alice | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $100 | $100 |

| Alice | Bought book | 2024-02-01 | -$20 | $80 |

This is different… Instead of just updating the existing balance, we’re adding a new row with the transaction details. The new columns we added earlier are helpful in understanding what happened to the account. We know that Alice had $100, then spent $20 when buying the book, and now has $80.

Time for more definitions: each row in this table is called an entry and the whole table is called a ledger.

Definition 3: Entry

A record of a transaction that happened to an account.

Definition 4: Ledger

A collection of entries for an account.

So far, we’ve updated only Alice’s ledger. Let’s take a look at Bob’s:

| Account | Description | Date | Amount | Balance |

| ------- | --------------- | ---------- | ------ | ------- |

| Bob | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $50 | $50 |

| Bob | Sold book | 2024-02-01 | $20 | $70 |

Now we have a ledger for each account. Great!

This system we implemented right now is called a single-entry bookkeeping system. Each account has its own ledger and we write down entries that affect one account at a time. This is a simple system that works well for small businesses or personal finances.

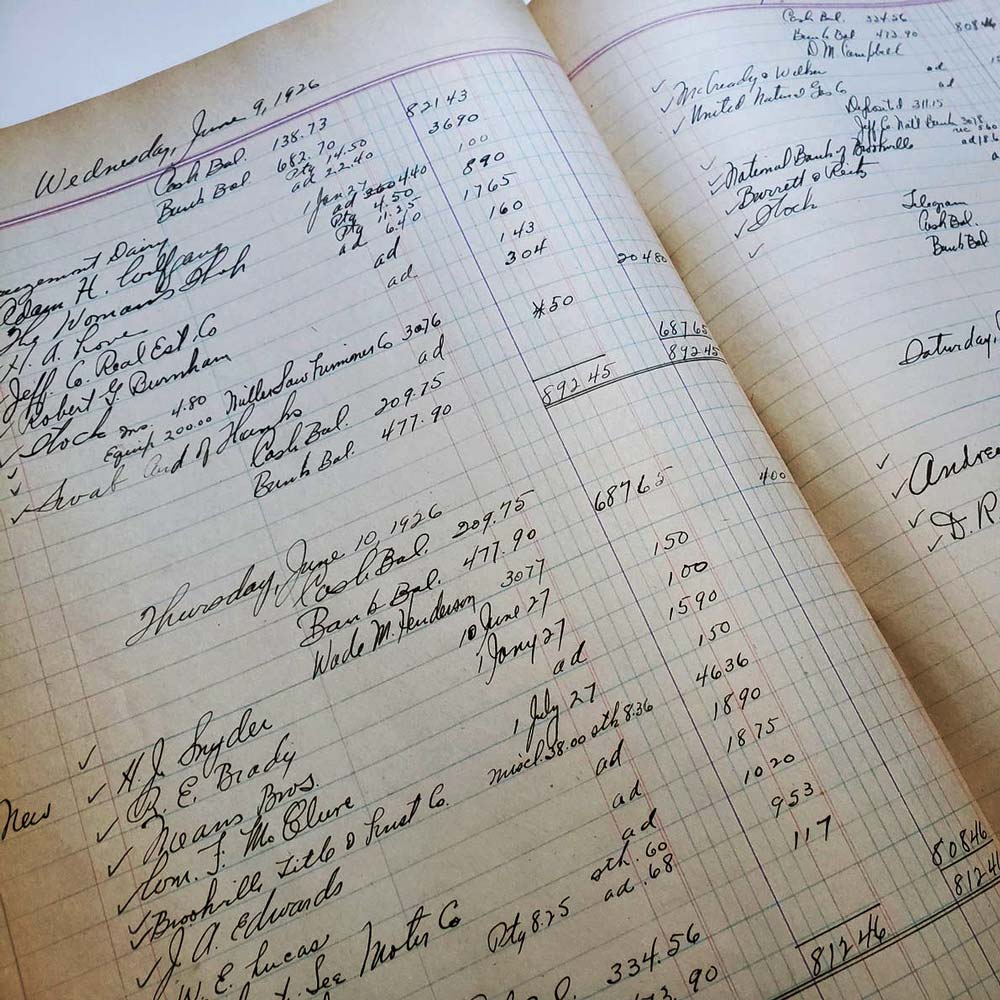

Ledgers are sometimes called journal or book because, in the past, they were physical books where accountants would write down transactions. In the modern world, though, they’re usually stored in a database.

An important characteristic of a ledger is that the data is immutable. Once an entry is written, it cannot be changed at all because we want to preserve the ledger’s full history. No more erasing or scribbling over entries.

This raises the question: what happens if we make a mistake?

Here’s an example. Say the correct price for the book is $30, but we wrote down $20. If we were in a mutable system, we could just update the amount in the original entry as follows:

| Account | Description | Date | Amount | Balance |

| ------- | --------------- | ---------- | ------ | ------- |

| Alice | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $100 | $100 |

| Alice | Bought book | 2024-02-01 | -$30 | $70 |

There are many problems with this approach though. We lose the history of the original amount. We can’t tell that we made a mistake and corrected it. We also can’t tell if the original amount was correct and we made a mistake in the correction.

Could we do better?

Yes! Instead of updating the original entry, we can write a new entry to cancel the old one and write a new one with the correct amount. Let’s see how this looks:

| Account | Description | Date | Amount | Balance |

| ------- | --------------- | ---------- | ------ | ------- |

| Alice | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $100 | $100 |

| Alice | Bought book | 2024-02-01 | -$20 | $80 |

| Alice | Correct book price | 2024-02-01 | $20 | $100 |

| Alice | Bought book | 2024-02-01 | -$30 | $70 |

The end result is the same as updating an entry in-place: the balance is $70. However, we can now see that we made a mistake and corrected it. We can also see the original amount and the reason for the correction. This gives us an audit trail of changes.

In a way, a ledger is similar to event sourcing in Computer Science. In event sourcing, we store events that happened in the system and use them to compute the current state of the system. This is in contrast to storing just the state of the system and updating it in-place. Event sourcing has many benefits, like being able to replay events or to rebuild the state of the system at any point in time.

If our system only cares about a single account at a time, a single-entry ledger system is enough. Think of a personal finance app that you use to keep track of your money or a gym that tracks how much their members paid for the service. However, financial systems are usually more complex than that and transactions typically involve multiple accounts at once.

For these complex scenarios, accountants developed a more robust system: double-entry bookkeeping.

Bookkeeping with Double-Entry Ledgers

Let’s revisit the example of Alice buying the book from Bob and see the ledgers for both accounts:

| Account | Description | Date | Amount | Balance |

| ------- | ------------------ | ---------- | ------ | ------- |

| Alice | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $100 | $100 |

| Alice | Bought book | 2024-02-01 | -$20 | $80 |

| Account | Description | Date | Amount | Balance |

| ------- | ------------------ | ---------- | ------ | ------- |

| Bob | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $50 | $50 |

| Bob | Sold book | 2024-02-01 | $20 | $70 |

Did you notice how the transactions are related to each other? The $20 Alice spent is the same $20 Bob received. We know that, but the system doesn’t, since we’re not explicitly stating this relationship in our ledgers. It could be the case the Alice bought the book from Bob and Bob received the money from Charlie. We can’t tell the difference when reading the ledgers.

A first step in making this relationship explicit is to group related entries into a transaction. Let’s add the Transaction column to our table:

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Amount | Balance |

| ------- | ---------- | ------------------ | ---------- | ------ | ------- |

| Alice | 1 | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $100 | $100 |

| Alice | 3 | Book sale | 2024-02-01 | -$20 | $80 |

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Amount | Balance |

| ------- | ---------- | ------------------ | ---------- | ------ | ------- |

| Bob | 2 | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $50 | $50 |

| Bob | 3 | Book sale | 2024-02-01 | $20 | $70 |

In this example, we have the following transactions:

- Transaction 1: Alice’s opening balance.

- Transaction 2: Bob’s opening balance.

- Transaction 3: Alice bought a book from Bob.

Now, we explicitly state that the $20 Alice spent is the same $20 Bob received. No more ambiguity.

Definition 5: Transaction

A group of related entries that affect different accounts.

The difference between our current system and the previous one is that we’re now grouping related entries into transactions. Since each transaction affects multiple accounts, we can now see how money flows between accounts. By adding transactions to the tables, we are now working with a double-entry bookkeeping system.

Traditionally, accountants would use two columns to represent the flow of money between accounts: credits and debits. When money leaves an account, the amounts goes in the credit column. Incoming money appears in the debit column.

Definition 6: Credit

An entry that represents money leaving an account.

Definition 7: Debit

An entry that represents money entering an account.

(Pro-tip: Ignore what you know about credit and debit cards for now. The terms are used somewhat differently in banking.)

When Alice pays Bob $20, we say Alice’s account is credited $20 and Bob’s account is debited $20. Let’s represent this in our table:

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Debit | Credit |

| ------- | ---------- | ------------------ | ---------- | ----- | ------ |

| Alice | 1 | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $100 | |

| Alice | 3 | Bought book | 2024-02-01 | | $20 |

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Debit | Credit |

| ------- | ---------- | ------------------ | ---------- | ----- | ------ |

| Bob | 2 | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $50 | |

| Bob | 3 | Sold book | 2024-02-01 | $20 | |

I wanted to make a few of points before continuing our journey.

First, the goal of double-entry bookkeeping is to reduce mistakes, especially the ones that are hard to notice. Remember that, for centuries, accountants were using pen and paper to keep track of insane amounts of money. Small mistakes could lead to big problems. Writing debits and credits in different columns, as we did above, reduces the chance of making mistakes. Your hand is literally moved to different places on the paper when writing debits and credits.

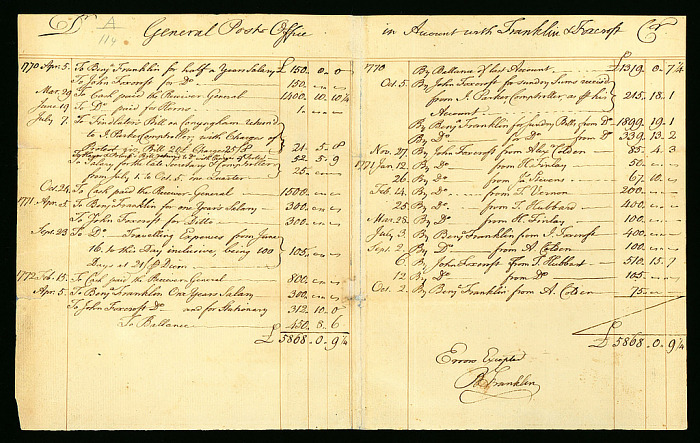

Real world accounting journals wouldn’t even put these columns side-by-side. Instead, they would be in different parts of the page. In fact, accounting journals were symmetrical: the left side was for debits and the right side, for credits. Something like this:

Debit Alice's account Credit

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

| Date | Description | $ | | Date | Description | $ |

| ---------- | --------------- | ---- | | ---------- | --------------- | ---- |

| 2024-01-01 | Opening balance | $100 | | | | |

| | | | | 2024-02-01 | Bought book | $20 |

This format is commonly referred to as a T-account (an analogy to the same: the top with the account name, the left side with debits, and the right side with credits). For this reason, many accountants will refer to debits as entries that go on the left side and credits as the ones that go on the right side.

Computer systems don’t need to use this format, though, as it doesn’t necessarily prevent software bugs. Instead, it is common to have a single amount column and another column to indicate whether the amount is a debit or a credit. For example:

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Type | Amount |

| ------- | ---------- | ------------------ | ---------- | ------ | ------ |

| Alice | 1 | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | Debit | $100 |

| Alice | 3 | Bought book | 2024-02-01 | Credit | $20 |

Second, notice how we’re using a positive number even when money is leaving Alice’s account. Historically, accountants don’t like negative numbers. In fact, Europeans weren’t a big fan of negative numbers until quite recently and modern accounting was heavily influenced by 13th-century Italian merchants. Computer systems are very good with negative numbers, though. Instead of having two columns, we could just use a single column and adopt a convention in which credits are negative and debits are positive, or vice-versa. For example:

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Amount |

| ------- | ---------- | ------------------ | ---------- | ------ |

| Alice | 1 | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $100 |

| Alice | 3 | Bought book | 2024-02-01 | -$20 |

If you pay close attention to this last example, this is exactly what we were doing before. The difference is that now we understand that the amount is negative because it’s a credit. (Technically, using negative numbers for credits might be a limitation if we’re trying to undo a credit entry without creating a debit entry, but we don’t need to be that picky for now.)

Finally, I’m not a big fan of old nomenclature for tradition’s sake. We could rename credits as outgoing money and debits as incoming money without losing precision. In my opinion, this is a bit less confusing.

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | ------------------ | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| Alice | 1 | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $100 | |

| Alice | 3 | Bought book | 2024-02-01 | | $20 |

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | ------------------ | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| Bob | 2 | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $50 | |

| Bob | 3 | Sold book | 2024-02-01 | $20 | |

Sweet!

A fundamental principle of double-entry bookkeeping is that the total amount of money in the system remains the same after each transaction. A particular account can increase or decrease its balance over time, but the sum of all balances must remain constant. Nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything is transacted. It is a closed system.

Definition 6: Double-Entry Ledger

A system of accounting where each transaction is recorded one or more entries. The amount of money leaving accounts is equal to the amount of money entering other accounts in every transaction.

Ok, you might be thinking: “Wait a minute, these opening balances go against what you just said!” and you’re right. Transactions 1 and 2 change the total amount of money in the system from $0 to $150. We should do better than stating a rule only to break it in the very next sentence.

Let’s assume all of the money that Alice and Bob have comes from a bank. Then, let’s create an account for this bank and use this account as the other side of the opening balance transactions.

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | -------------------------- | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| Bank | 1 | Alice's opening balance | 2024-01-01 | | $100 |

| Bank | 2 | Bob's opening balance | 2024-01-01 | | $50 |

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | -------------------------- | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| Alice | 1 | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $100 | |

| Alice | 3 | Bought book | 2024-02-01 | | $20 |

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | -------------------------- | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| Bob | 2 | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $50 | |

| Bob | 3 | Sold book | 2024-02-01 | $20 | |

In this example, we don’t care where the opening balances come from exactly. We just need to make sure money is coming from somewhere. The bank account is a kind of phony account that is there just to help us follow the rules. In accounting terms, it is called a contra account to the other accounts. The important thing is that all transactions are balanced, i.e., “credits equal debits”. It acts as a simple checksum that helps accountants to catch mistakes, especially when they were doing things manually.

Definition 7: Contra Account

An account that is used to offset another account. It is used to keep the accounting equation in balance.

Our system is now complete. We have a double-entry ledger system that keeps track of money flowing between accounts. We can answer many questions about the financial situation of Alice and Bob and we have a clear audit trail of all transactions that happened.

Let’s consider a more complex example. When Alice buys the book, she accidentally uses the wrong credit card and needs to pay $2 in foreign exchange fees. Bob, on the other hand, pays $2 in sales taxes to the government, $1 in credit card fees. How do we keep track of this?

The secret in double-entry bookkeeping is to use accounts for everything. As we did before, we model this flow by creating new accounts: one for the credit card company and another for the tax authority. Then, when creating the transaction, we add new entries as necessary.

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | -------------------------- | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| Bank | 1 | Alice's opening balance | 2024-01-01 | | $100 |

| Bank | 2 | Bob's opening balance | 2024-01-01 | | $50 |

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | -------------------------- | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| Alice | 1 | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $100 | |

| Alice | 3 | Bought book | 2024-02-01 | | $20 |

| Alice | 3 | Foreign exchange fee | 2024-02-01 | | $2 |

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | -------------------------- | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| Bob | 2 | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $50 | |

| Bob | 3 | Sold book | 2024-02-01 | $20 | |

| Bob | 3 | Sales tax | 2024-02-01 | | $2 |

| Bob | 3 | Credit card fee | 2024-02-01 | | $1 |

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | -------------------------- | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| CC | 3 | Alice's credit card fee | 2024-02-01 | $2 | |

| CC | 3 | Bob's credit card fee | 2024-02-01 | $1 | |

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | -------------------------- | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| Tax | 3 | Bob's sales tax | 2024-02-01 | $2 | |

We modified transaction 3 as follows:

- Alice pays $20 to Bob and $2 to the credit card company.

- Bob receives $20 from Alice, pays $2 to the tax authority, and $1 to the credit card company.

- The credit card company receives $2 from Alice and $1 from Bob.

- The tax authority receives $2 from Bob.

Notice that transaction 3 has more than two entries. It has eight entries, to be precise. This is perfectly fine! We can have as many entries as we need to represent the flow of money between accounts as long as the transaction is balanced, i.e., credits = debits.

It is a common mistake to think that double-entry bookkeeping limits transactions to two entries at a time. The technique is called “double-entry” not because there are only two entries, but because each transaction has two sides: one side where money leaves an account and another side where money enters another account. I guess “many-entry bookkeeping” doesn’t sound as good.

Double-Entry Bookkeeping is a Directed Graph

I hope these concepts are clear so far. We have accounts, entries, transactions, incoming money, and outgoing money. With practice, you’ll be able to read and write these tables with ease.

But I have a confession to make: I’m a visual person. I like to draw and see things when I’m learning. So I started to think: how can we visualize this data in a way that makes sense to me? After using double-entry bookkeeping for a while in my personal finances and trying to come with a visualization for my ledgers, it finally clicked: we’re modeling money flow as a directed graph.

Think about this: An account is a node in the graph, a credit entry is an outgoing edge with an amount of money leaving this node whereas a debit is an incoming edge with money flowing to another node. A transaction, then, groups and enforces a condition on a set of edges: the outgoing edges must have the same sum of money as the incoming edges.

Let’s take a look at the example we’ve been using so far. First, we start with Alice’s and Bob’s accounts and the money they stored in the bank:

A few comments on this graph:

- An account is a round node with the account name.

- A transaction is a square node with the transaction number.

- A credit entry goes from an account to a transaction.

- A debit entry goes from a transaction to an account.

- The entry’s amount of money is written on the edge.

- An account’s balance is the sum of the amounts of the incoming edges minus the sum of the amounts of the outgoing edges.

We can see that transaction 1 moves $100 from the bank to Alice. Transaction 2 moves $50 from the bank to Bob. The total amount of money in the system is $150.

Then, Alice buys a book from Bob:

We can see that transaction 3 moves $20 from Alice to Bob. Hence, Alice has $80 and Bob, $70.

We haven’t added fees and taxes yet. Let’s do this:

Oof, that’s a lot of edges! Transaction 3 is very complex as it conflates what Alice is paying Bob with the fees and taxes they pay to other parties. We could make this easier by splitting this transaction into two smaller ones:

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | -------------------------- | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| Bank | 1 | Alice's opening balance | 2024-01-01 | | $100 |

| Bank | 2 | Bob's opening balance | 2024-01-01 | | $50 |

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | -------------------------- | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| Alice | 1 | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $100 | |

| Alice | 3 | Bought book | 2024-02-01 | | $22 |

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | -------------------------- | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| Bob | 2 | Opening balance | 2024-01-01 | $50 | |

| Bob | 3 | Sold book | 2024-02-01 | $19 | |

| Bob | 4 | Sales tax | 2024-02-01 | | $2 |

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | -------------------------- | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| CC | 3 | Transaction fee | 2024-02-01 | $3 | |

| Account | Transaction | Description | Date | Incoming | Outgoing |

| ------- | ---------- | -------------------------- | ---------- | -------- | -------- |

| Tax | 4 | Bob's sales tax | 2024-02-01 | $2 | |

And as a graph:

We simplified the transactions a little bit:

- Alice sees $22 leaving her account, but Bob only receives $19. The remaining $3 goes to the credit card company.

- Bob pays sales taxes in a different transaction.

Regardless of how we model the transactions, the account balances are the same. Alice has $78, Bob has $67, the tax authority has $2, and the credit card company has $3. It is the accountant’s job to decide how to group transactions and entries in a way that makes sense for the business as the bookkeeping system is flexible enough to accommodate different needs.

These simple examples show how we can visualize money flow in a double-entry bookkeeping system as a directed graph. The graph grows over time as new transactions are added, but it’s properties remain the same. In my opinion, understanding bookkeeping as a graph is a powerful way to reason about many accounting concepts. Suddenly, things as balance sheets, income statements, and cash flow statements are just visualizations of this graph. Categories such as assets, liabilities, equity, income, and expenses are just groups of nodes in the graph and it is quite easy to understand whether credits or debits increase their balances. It’s a way to make accounting more intuitive and less intimidating to me!

We could go on and on with this example, adding more complexity to the transactions, creating new accounts, and visualizing the graph as it grows. But I think we did a great job today and should take a well-deserved break.

Takeaways

In this article, we’ve covered the basics of bookkeeping. We started with a simple system that only kept track of balances, evolved it into a single-entry and, later, into a double-entry ledger system that models money flow between accounts. We’ve seen how to represent transactions as entries in a ledger and how to group related entries into transactions. Finally, we’ve seen how to visualize a double-entry ledger as a directed graph.

In the next article, we’ll dive deeper into basic accounting concepts and see how they relate to the graph representation we’ve seen here.

Resources

When studying these concepts, I found the following resources particularly helpful:

- Accounting & Financial Statement Analysis: Complete Training: A crash course in accounting in Udemy. It was my introduction to the topic and I highly recommend it.

- Mastering Accounting by George Bright and Michael Herbert: A textbook that covers accounting from the basics to more advanced topics. Another great resource to deepen my understanding of accounting.

- Beancount’s documentation has a great explanation of accounting as a graph over time. It was a big inspiration for this article.

- Modern Treasury has a great series of articles that explain accounting concepts for developers. It is another big inspiration.

- This particular thread on Hacker News. Some comments are gold!

- Plain text accounting is a small but engaged community that uses plain text files and command-line tools to keep track of their finances. I use hledger for my personal finances.